In the late 1970s, I approached my studies for an MSc in Health Sciences with an idealistic goal to create ways to promote wellness and prevent disease. Although life took me in a different direction, I’ve tried to stay caught up on healthcare.

In the late 1970s, I approached my studies for an MSc in Health Sciences with an idealistic goal to create ways to promote wellness and prevent disease. Although life took me in a different direction, I’ve tried to stay caught up on healthcare.

Recently, I’ve noticed a committed effort in this country to assist the under-served: food services that offer nutritional training as an outpatient service in hospitals and training in healthy eating for patients; outpatient and home support for treatment and prevention for diabetes, obesity, heart disease, cancer sufferers; school lunches and Pre-K programs. I hadn’t been aware of the extent, or creativity, of the outreach of caregiving professionals. We’re on our way to understanding that prevention is preferable to treatment.

The bad news is that some easily treatable or preventable conditions (diabetes, heart conditions, cancer, obesity) are not garnering the necessary buy-in from patients to make the needed healthy choices.

With the best will in the world, providers – intent on designing outreach programs to encourage behavioral change and choice – are facing non-compliance: even with adequate funding, multi-faceted prevention services, and supervised support, patients are resisting and not adopting the necessary changes to generate long term health. What’s going on?

STATUS QUO

The problem is that the methods we’re using to inspire healthful behavior aren’t facilitating compliance. But with a shift in thinking, buy-in is achievable. It’s a belief-changing thing, not a behavior-change thing.

I’ll begin with a brief discussion of change and how we unwittingly fight to remain stable regardless of its (in)effectiveness. Buy-in is a change management problem.

We’re intelligent. We know smoking and sugar are bad, that exercise and fresh veggies are good, yet we continue to smoke and eat processed foods. We know that telling, advising, or offering ‘relevant’ and ‘rational’ information is largely ineffective and invokes resistance, yet we continue to tell, advise, and suggest, knowing that the odds of success are against us and blaming the Other for non-compliance.

When faced with the need to change, we tend to continue our current behaviors with just a few shifts, hoping we’ll get different results (Hello, Einstein.).

The problem is that change is a systems problem that demands buy-in from the very things that created the problem in the first place – much more intricate than knowing there’s a problem.

Let’s look at the problem by understanding why people keep doing what they do. I’ll be discussing this in terms of systems.

For those interested in a deeper discussion, I’ve broken down change and decision making from the brain in my new book HOW? Generating new neural circuits for learning, behavior change, and decision making.

OUR STATUS QUO LIKES STABILITY

Each person, each family (everyone, actually), is a system of rules and goals, beliefs and values, history and foundational norms often called our Mental Models our status quo. It represents who we are and the organizing principles that we wake up with every morning; it’s habitual, normalized, accepted, and replicated day after day – including what created the identified problem to begin with – with the problems baked in. Unfortunately our automatic patterns cause us to keep doing what we’ve always done and has become comfortable.

Any proposed change challenges the status quo and invites risk and possible disruption. When a problem shows up, diabetes for example, the patient has a dilemma: either continue their comfortable patterns and be assured of a continued problem, or dismantle the status quo and risk disruption with unknowable consequences.

How does she get up every day if she needs to eat differently and must convince her family that the food they’ve been eating for generations isn’t healthy? How does she avoid dessert when the family is celebrating? And the family’s favorite recipe is her cookies!

Change means the status quo has to reconfigure itself around new/different/unknown rules, beliefs, and outcomes to become something that can maintain itself with the ‘new’ as normalized. Because – and this is important to understand – until people and their unconscious norms

- recognize that something is wrong/ineffective,

- recognize that whatever they’ve been doing unconsciously has created (and will maintain) the problem,

- know how to make congruent change that includes core values and systems norms,

- know exactly the level of disruption that will occur to the status quo, and

- make a belief shift that is acceptable to the rest of the system and enables new behaviors,

they will not change, regardless of its efficacy of the value of the solution.

In other words, until or unless someone understands their risk of change, AND are willing/able to do the deeply internal work of designing new habits, beliefs, and goals, AND manage any fallout, people will not change regardless of their need or the efficacy of your solution.

UNCONSCIOUS PATTERNS HARD TO NOTICE

Why isn’t a rational argument, or an obvious problem, enough to inspire behavior change? Because we’re dealing with long-held and largely unconscious patterns, habits, and normalized activities and beliefs that become part of our neural circuitry. And because we’re trying to push change from the outside – usually through information, advice, and activities – before the system has figured out how to change in the least risky way.

Rational argument is ignored because our unconscious fights to maintain the status quo: we’ve been ‘like this’ for so long and it’s been ‘good enough’ to keep us stable. Change must be agreed to from our deepest norms before being willing to change behaviors. And until then, we can’t even accurately hear incoming data if it runs counter to our beliefs.

THE INTRICACY OF BUY-IN

Change is a belief change issue. By focusing on behavior change before facilitating belief change, we’re putting our status quo at risk. Let’s look at what a behavior is.

Behaviors are merely the expression – the representation, the output – of our beliefs. Think of it this way: behaviors express our beliefs much like the output of a software program is a result of the coding in the programming. To change the output, you don’t start by changing the functionality; you first change the coding which automatically changes the functionality. Like a dummy terminal, our behaviors only represent our internal programming.

WHY PROFESSIONALS DON’T PROMOTE CHANGE

How does this all apply to Healthcare? Our current healthcare system considers providers to be experts with the ‘right’ answers. Providers wrongly believe that if they share, advise, gather, or promote the right information with rational reasons why change is necessary, Others will comply. But our patients and clients

- hear us through biased filters and cannot hear our message as meant;

- feel pushed to act in ways they’re unaccustomed to or that go against their beliefs;

- resist and reject when expected to act in ways outside their norm;

- lose trust in us when we push them.

Because of their history, because brains often mistranslate incoming words, because the new may negatively touch their beliefs – for any number of reasons – information ‘in’ without systemic change may not prompt a hoped-for response.

So how can we effect compliance if offering information or diets or exercise programs, for example, isn’t effective?

PEOPLE CAN ONLY CHANGE THEMSELVES

Start by recognizing that people must change themselves. Instead of seeking better and better ways to offer advice (and getting rejected and ignored), we must help people make their own discoveries and systemic changes.

Here are some ways you can enter a change conversation to enable buy-in and avoid resistance:

- Shift your goal. Your job is to help Another be all they can be. It’s not about you getting them to accept the change you believe necessary, but enabling them to design the change they need, in a way that concurs with their beliefs and values.

- Enter differently. Enter with a goal/outcome of facilitating change and buy-in, not to change behavior. They must change their own behavior. From within. Their own way.

- Examine the status quo. First help Others recognize and assemble all of the elements that created and maintain their status quo – not merely the ones involved with the problem as you perceive it, but the entire system that created and maintains it. Outsiders can’t recognize the full complement of givens within another’s status quo. Starting with a focus on what you perceive is the problem (or the Other recognizes as a problem) inspires rejection.

- Traverse the brain’s steps to change. There are 13 steps to change that must be traversed for all change to occur. Unless all – all – of the elements have been included, recognize a need to change, and know precisely how to make the appropriate shifts so a stable systems results, they will resist.

- Behavior is an expression and not a unique act. We must recognize that exhibited behaviors are expressing beliefs. Change must occur at the belief level. Trying to push or inspire behavior change is at the wrong level and causes resistance.

- Everyone has their own answers. They may not be what you would prefer and might not make sense given the outcomes. Help them recognize how and when and if to change. But not using information as it can’t be understood.

Here are some examples of how I’ve added Change Facilitation to elements of health care in a way that promotes belief change first, ideas that might inspire you to think differently:

Intake forms: instead of merely gathering the data you think you need (which you’ve inadvertently biased), why not enlist patient buy-in at the earliest opportunity? It’s possible to add a few Facilitative Questions (I developed a form of question that enables unbiased systemic change and decision making and eschews information gathering. See examples below.) to your forms to start the patient off recognizing you, and including you, as a partner at the very beginning of your relationship and their route to healthful choices:

We are committed to helping you achieve the goals you want to achieve. What would you need to see from us to help you down your path to health? What could we do from our end that would best enable you to make whatever changes you might want to make?

Group prevention/treatment: instead of starting off by sharing new food or exercise plans, let’s add some change management skills to the goals of the group. By giving them direction around facilitating each other’s change issues, you can enable the group to discuss potential fallout to any proposed change, determine what change would look like, and begin discussions on how to approach each aspect of risk together to recognize different paths to success. Then the whole group can support each other’s different paths to success:

As we form this group, what would we all need to believe to incorporate everyone’s needs into our goals? If there are different goals and needs, how do we best support each other to ensure we each achieve our goals?

Doctor/patient communication: instead of a medical person offering ideas or information, make sure you achieve buy-in for change first. This encourages a patient to self-examine their unconscious behaviors while trusting the provider.

It seems you are suffering from diabetes. We’ve got nutritional programs, group support, book recommendations. But I’d first like to help you determine what health means for you. How will you know when it’s time to consider shifting some of your health choices to open up a possibility of treating your diabetes in a way that doesn’t diminish your lifestyle?

A healthy patient, or any desire to change in a way that benefits a more balanced life, is the goal. Be willing to enable change and compliance, rather than attempt to manage it, influence it, or control it. I’ve got some articles on these topics if you wish further reading: Practical Decision Making; Questioning Questions; Trust – what is it and how to initiate it; Resistance to Guidance; Influencers vs Facilitators.

______________________

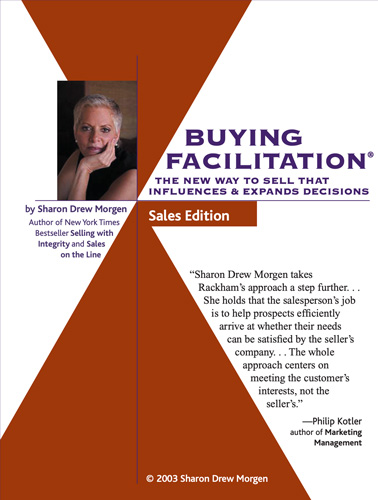

Sharon-Drew Morgen is a breakthrough innovator and original thinker, having developed new paradigms in sales (inventor Buying Facilitation®, listening/communication (What? Did you really say what I think I heard?), change management (The How of Change™), coaching, and leadership. She is the author of several books, including her new book HOW? Generating new neural circuits for learning, behavior change and decision making, the NYTimes Business Bestseller Selling with Integrity and Dirty Little Secrets: why buyers can’t buy and sellers can’t sell). Sharon-Drew coaches and consults with companies seeking out of the box remedies for congruent, servant-leader-based change in leadership, healthcare, and sales. Her award-winning blog carries original articles with new thinking, weekly. www.sharon-drew.com She can be reached at sharondrew@sharondrewmorgen.com.

2 thoughts on “Facilitating Compliance: helping patients choose health”

Smoking was found to be embedded in a network six degrees deep.

My mom used to tell us she loved us by cooking. She was a great cook. My diabetes left her with no way to tell me she loved me. She did not learn to omit carbos and fruit. I loved all of it, but I went on the South Beach phase one and stayed there. Not ideal, but it was what I did. She was in my second degree network. I’m an introvert, so I don’t have a deep network, so I could change what needed to be changed, except for mom.

OT: If you mom is a great cook, realize that she won’t like nursing home food.

Pingback: Putting People First: the path to Customer Centricity, essay | Sharon-Drew Morgen