As instructors you’re committed to collaborating with your students, inspiring their creativity and sparking their original ideas. You pose interesting questions to enthuse them and work hard at offering knowledge in a way that inspires their learning.

As instructors you’re committed to collaborating with your students, inspiring their creativity and sparking their original ideas. You pose interesting questions to enthuse them and work hard at offering knowledge in a way that inspires their learning.

But are they hearing what you intend to convey?

When I heard two highly intelligent people having a conversation in which neither were directly responding to each other (“Where should my friends pick me up?” “There’s parking near the bottom of the hill.”) I became curious. Were they hearing different things that caused disparate responses?

I spent the next 3 years studying how brains listen and writing a book on it (WHAT? Did you really say what I think I heard?). I ended up learning far more than I ever wanted to: like most people, I had assumed that when I listened I accurately heard someone’s intended message. I was wrong.

HOW BRAINS LISTEN

Turns out there’s no absolute correlation between what a Speaker says and what a Listener hears – a very unsatisfactory reality when our professions are based on offering content that is meant to be understood and retained. Sadly there’s a probability that students are not taking away what we’re paid to teach them.

To give you a better idea of how this happens and how automatic and mechanical this process is, here are the steps brains perform when hearing spoken words.

1. A message (words, as puffs of air, initially without meaning) gets spoken and received as sound vibrations.

2. Dopamine processes incoming sound vibrations, deleting and filtering out some of them according to relevance to the Listener’s mental models.

3. What’s left gets sent to a CUE which turns the remaining vibrations into electrochemical signals.

4. The signals then get sent to the Central Executive Network (CEN) where they are dispatched to a ‘similar-enough’ neural circuit for translation into meaning.

Note: The preferred neural circuits that receive the signals are those most often used by the Listener, regardless of their relevance to what was said.

5. Upon arrival at these ‘similar-enough’ circuits, the brain discards any overage between the existing circuit and the incoming one and fills in any perceived holes with ‘other’ signals from neighboring circuits.

What we ‘hear’ is what remains. So: several deletions, a few additions, and translation into meaning by circuits that already exist.

In other words, what we think we hear, what our brain tells us was said, is some rendition of what a Speaker intends to convey biased by our own history. And when applying these concepts to training and instruction, neither the instructor nor the student knows the distance between what was said and what was heard.

I lost a business partner who believed I said something I would never have said. He not only didn’t believe me when I told him what I’d actually said, but he didn’t believe his wife who was standing with us at the time. “You’re both lying to me! I heard it with my own ears!” and he stomped out of the room, never to speak to me again.

HOW TO CONFIRM STUDENTS HEAR US

What does that mean for instructors? It means we have no idea if some/all/few of the students hear precisely what we are trying to convey. Or they might hear something similar, or something that offends them. They may hear something quite comfortable or something vastly different. They may misinterpret a homework assignment or a classroom instruction. It means they may not retain what we’re offering.

To make sure students understand what we intend to share, we must take an extra step when we instruct. Instead of merely assuming we’re presenting good content or asking creativity-building questions, we must assume we don’t know what the students have heard, regardless of how carefully we’ve worded our message.

In smaller classrooms I suggest we ask:

Can you each tell me what you heard me say?

Or, with a large class, say the same thing in several different ways: you can begin by explaining –

Because of the way brains hear incoming words, you’ll each translate what I’m saying differently. To make sure we’re all doing the same assignment, I’m going to tell you the homework assignment in several different ways:

Write a 3-page paper on [how your creativity is inspired]. Let me repeat this in a different way:

In 3 pages, explain what’s stopping you from [being as creative as you can be]. Or maybe this is clearer for you:

How do you ‘do’ your [creativity to end up with a new concept]? Explain in a 3 page paper. Or:

Hand in a 3 page paper that explains [your thinking process that triggers new ideas].

It might sound like extra work but the learners will:

- understand what you intend for them to do (in their own way, but they’ll get the meaning);

- promote uniform topic discussions;

- eschew confusion and inspire original ideas;

- circumvent regurgitation.

Since students sometimes fear offering original thoughts as they don’t want to hand in a ‘wrong’ answer, this type of exposition ensures they’ll all hear your intent and be willing to share their authentic responses. And, they’ll understand that if they don’t precisely grasp what their instructor is offering, it’s their brain’s fault.

______________________

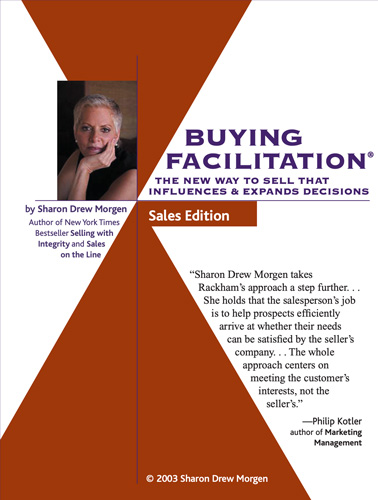

Sharon-Drew Morgen is a breakthrough innovator and original thinker, having developed new paradigms in sales (inventor Buying Facilitation®, listening/communication (What? Did you really say what I think I heard?), change management (The How of Change™), coaching, and leadership. She is the author of several books, including her new book HOW? Generating new neural circuits for learning, behavior change and decision making, the NYTimes Business Bestseller Selling with Integrity and Dirty Little Secrets: why buyers can’t buy and sellers can’t sell). Sharon-Drew coaches and consults with companies seeking out of the box remedies for congruent, servant-leader-based change in leadership, healthcare, and sales. Her award-winning blog carries original articles with new thinking, weekly. www.sharon-drew.com She can be reached at sharondrew@sharondrewmorgen.com.