What if it were true that we only understand a fraction of what others say to us? And if true, what can we do about it?

What if it were true that we only understand a fraction of what others say to us? And if true, what can we do about it?

As someone who has taken great pride in accurately hearing what others say, I was annoyed to discover that it’s pretty impossible for any listeners to achieve any consistent level of accuracy. The problem is not the words – we hear those, albeit we only remember them for less than 3 seconds and not in the proper order (Remember the game of Telephone we played as kids?). The problem is how we interpret them.

OUR BRAINS RESTRICT ACCURACY

When researching my new book What? Did you really say what I think I heard? I learned that our brains arbitrarily delete or redefine anything our Communication Partners (CPs) say that might be uncomfortable or atypical. Unfortunately, we then believe that what we think we’ve heard – a subjective translation of what’s been said – is actually what was said or meant. It’s usually some degree of inaccurate. And it’s not our fault. Our brains do it to us.

Just as our eyes take in light that our brains interpret into images, so our ears take in sound that our brains interpret into meaning. And because interpreting everything we hear is overwhelming, our brain takes short cuts and habituates how it interprets. So when John has said X, and Mary uses similar words or ideas days or years later, our brains tell us Mary is saying X. It’s possible that neither John nor Mary said X at all, or if they did their intended meaning was different; it will seem the same to us.

Not only does habit get in the way, but our brains use memory, triggers, assumptions, and bias – filters – to idiosyncratically interpret the words spoken. Everything we hear people say is wholly dependent upon our unique and subjective filters. It’s automatic and unconscious: we have no control over which filters are being used. Developed over our lifetimes, our filters categorize people and social situations, interpret events, delete references, misconstrue ideas, and redefine intended meaning. Without our permission.

As a result, we end up miscommunicating, mishearing, assuming, and misunderstanding, producing flawed communications at the best of times although it certainly seems as if we’re hearing and interpreting accurately. In What? I have an entire chapter of stories recounting very funny conversations filled with misunderstandings and assumptions. My editor found these stories so absurd she accused me of inventing them. I didn’t.

It starts when we’re children: how and what we hear other’s say gets determined when we’re young. And to keep us comfortable, our brains kindly continue these patterns throughout our lives, causing us to restrict who we have relationships with, and determine our professions, our friends, and even where we live.

HOW DO WE CONNECT

Why does this matter? Not because it’s crucial to accurately understand what others want to convey – which seems obvious – but to connect. The primary reason we communicate is to connect with others.

Since our lives are fuelled by connecting with others, and our imperfect listening inadvertently restricts what we hear, how can we remain connected given our imperfect listening skills? Here are two ways and one rule to separate ‘what we hear’ from the connection itself:

- For important information sharing, tell your CP what you think s/he said before you respond.

- When you notice your response didn’t get the expected reaction, ask your CP what s/he heard you say.

Rule: If what you’re doing works, keep doing it. Just know the difference between what’s working and what’s not, and be willing to do something different the moment it stops working. Because if you don’t, you’re either lucky or unlucky, and those are bad odds.

Now let’s get to the connection issue. Here’s what you will notice at the moment your connection has been broken:

- A physical or verbal reaction outside of what you assumed would happen;

- A sign of distress, confusion, annoyance, anger;

- A change of topic, an avoidance, or a response outside of the expected interchange.

Sometimes, if you’re biasing you’re listening to hear something specific, you might miss the cues of an ineffective reaction. Like when, for example, sales people or folks having arguments merely listen for openings to say that they want, and don’t notice what’s really happening or the complete meaning being conveyed.

Ultimately, in order to ensure an ongoing connection, to make sure everyone’s voice is heard and feelings and ideas are properly conveyed, it’s most effective to remove as many listening filters as possible. Easier said than done, of course, as they are built in. (What? teaches how to fix this.) In the meantime, during conversations, put yourself in Neutral; rid yourself of biases and assumptions when listening; regularly check in with your Communication Partner to make sure your connection is solid. Then you’ll have an unrestricted connection with your CP that enables sharing, creativity, and candor.

__________

Sharon-Drew Morgen is the author most recently of What? Did you really say what I think I heard? as well as self-learning tools and an on-line team learning program – designed to both assess listening impediments and encourage the appropriate skills to accurately hear what others convey.

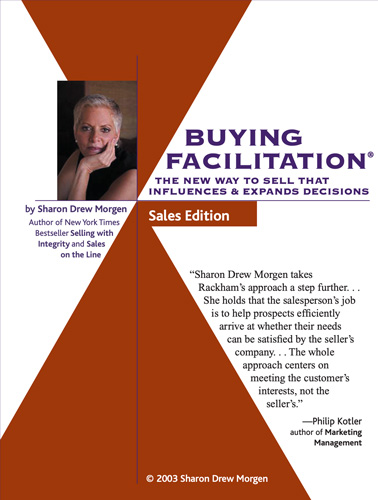

Sharon-Drew is also the author of the NYTimes Business Bestseller ‘Selling with Integrity’ and 7 other books on how decisions get made, how change happens in systems, and how buyers buy. She is the developer of Buying Facilitation® a facilitation tool for sellers, coaches, and managers to help others determine their best decisions and enable excellence. Her award winning blog sharondrewmorgen.com has 1500 articles that help sellers help buyers buy. Sharon-Drew recently developed 3 new programs for start ups.

She can be reached at sharondrew@

6 thoughts on “Why Do We Listen To Each Other?”

Pingback: What Makes A Decision Irrational? | Sharon-Drew Morgen

Pingback: What Makes A Decision Irrational? – buyingfacilitation.com/blog

Pingback: What Makes A Decision Irrational? | What? Did You Really Say What I Think I Heard?

Sharon-Drew, what a GREAT reveal of the facts in this phenomenon. So much our of relatedness to one another is so dependent upon whether or not we’ve heard heard each other. In particular, it’s mind-blowing to think about how much emphasis our own egos put on whether or not we’ve been accurately heard by someone else. How many times have we said to someone else (or thought to ourselves) or had said to us: “You must not care about me as much as I thought you did since you didn’t really hear (or remember) what I said.” And so, we judge others, and even ourselves, harshly for not being understood or remembered! We need to practice compassion for others and ourselves in light of this profound information that you’ve shared here! Thank you so much for posting. By the way, there’s also a great TED Talk related to our perceptions of the world in front of us and each other. as well as, how our minds and choices are then impacted: Emily Balcetis: Why some people find exercise harder than others [https://goo.gl/FE9UBV]. ~Achievement Coach Greg Kilgore, http://www.360ACHIEVE.com

Pingback: What Makes A Decision Irrational? - StrategyDriven

Pingback: Sharon-Drew Morgen » What Makes A Decision Irrational?