INTRODUCTION

There’s a long-held belief that training causes learning by sharing knowledge in a way that imparts understanding and retention if presented creatively and practiced diligently. Whole professions focus on developing creative training materials; behavior scientists study ways to promote ‘active learning’; instructional design integrates the visual, auditory, and kinesthetic learning styles.

However, according to Google and Harvard studies, 90% of learning is not retained. Why? Are students not motivated? Are Trainers not doing their jobs? Do we need better experiential exercises? What’s going on?

I suggest it’s not the students, the motivation, the trainer, or the material being trained. I suggest it’s a brain change issue: current training models, while certainly dedicated to imparting knowledge in creative, constructive ways, may not be developing the necessary neural circuitry for Learners to fully comprehend, retain, or retrieve the new information.

In this paper I’ll explain why training, information-sharing and experiential practice don’t necessarily impart learning: without proper neural circuitry there may not be a place in a Learner’s brain for our material to be accepted, stored, or translated for full understanding and later use.

WHO AM I?

As a child with undiagnosed Asperger’s, I was frequently misunderstood and confused: choices that seemed fine to me were deemed inappropriate. And even as a cheerleader with great grades, I couldn’t make friends.

For years I valiantly tried to fit in, going so far as learning sequences of responses I heard from neurotypicals so I’d seem ‘normal’ (I still don’t understand why “Fine, thanks.” is the norm when someone says “How are you?”.) but failed regardless of my efforts. Out of desperation I decided to figure out how to get into my brain to make other choices directly from wherever the flawed behaviors originated. Frankly, I had no idea how to even think about those things. Indeed, it took me decades to figure it out.

As an original thinker even as a teenager, and with ‘brain change’ as my Aspie ‘topic’, I researched diligently to understand how brains learn and change. But there was little data available decades ago; the field of neuroscience certainly didn’t yet exist. I scoured libraries and magazines (I still assiduously read research papers and books on brains) to figure out: how do brains determine what to do or say? How do they retain knowledge? Do brains listen accurately? How do brains make decisions? How can I mitigate my behaviors if they’re automatically generated and outside my awareness?

Over the next decades I realized that all that we are, hear, see, and think, comes from our brain, and that all activities emanate from existing neural circuitry. I identified the steps brains take to decision making and congruent change; learned how each brain region works, sends and receives signals, and collaborates with other regions to cause action.

Eventually I designed systemic brain change models to facilitate conscious choice and behavior change in:

- business (Buying Facilitation®, Change Facilitation) – to facilitate the risk management everyone must address on route to change;

- communication (Listening Facilitation) – to facilitate our brain’s ability to hear others without bias;

- healthcare (Decision Facilitation) – to help patients change behaviors permanently and congruently, from their own values;

- learning (Learning Facilitation) – to generate new neural circuits so learners can store, understand, use, and retain new information;

- a brain directional question (Facilitative Question) that gets to specific neural circuits and enables values-based decision making.

This paper examines why current training causes low retention rates, and details a methodology that installs new neural circuits directly in a Learner’s brain: Learning Facilitation first disengages the mind (that translates the brain’s largely electrochemical processes into action) from the brain to generate new neural circuits to house, translate, and retain the new information.

TRAINING IS A PROBLEM FOR THE BRAIN

Note: For this paper, I’ll focus on the type of training that uses words to offer information rather than graphics or video games.

Current training models use ‘information transfer’ (human, electronic, visual, technological) as the guideline, assuming that, with proper delivery and enough practice, Learners will acquire new information. But it’s not so simple: just because new information is needed, offered in a stimulating way, or practiced diligently doesn’t mean there’s a corresponding connection between information-in, brain processing, and subsequent action.

Brains, it turns out, are merely mechanical devices that ascribe no meaning. As such, everything we think, hear, see, or understand is the result of how our brain links electrochemical signals from its different regions into patterns of associative communications (called neural circuits) that instruct our mind to act.

As per the mind -> brain interchange, hearing, understanding, and acting on external instruction are not straight forward: Learners may not accurately ‘hear’ or understand what’s been said; the incoming information may be sent to the wrong circuits and mistranslated; and there may be no place to store the new for later use.

As you’ll see, by the time a Learner’s mind receives any content, some percentage of the incoming knowledge has been filtered, deleted, or misconstrued by the brain. Learners have no way of knowing of any disparities between what they think they’ve heard and what the Trainer is offering. Sadly, it’s not until sometime afterwards that it becomes apparent the Learner hasn’t maintained the knowledge.

The 10% of Learners who retain what we offer have some history of the presentation content with existing circuitry that merely needs updating. But Learners who are unfamiliar with the content, or who have an unconscious bias around similar subjects, have no place in their brain to understand/translate or store the content for later use. Our current training doesn’t construct a home for the new knowledge to be parked.

By designing training that enables a Learner’s brain to construct specific neural circuits to house what we’re teaching, a much higher percentage of learners will understand and retain the new knowledge.

HOW BRAINS RECEIVE INFORMATION

Information, it turns out, is the last thing Learners need in order to learn and retain something new. By offering information first there’s a chance it will be resisted, rejected, misunderstood, or forgotten. As I’ll explain, brains can’t even ‘hear’ incoming information accurately.

It’s possible to design training in a way that generates neural circuits within the Learner’s brain before information is presented and before it gets compromised. Here’s some background on how brains prompt our minds to cause action.

Each of us is a self-contained, unique, and idiosyncratic system of beliefs, history, mental models, values, experiences etc. – our system – that become filters for all we experience. Our system, the status quo, is largely unconscious, structured around who we identify as and believe ourselves to be. In other words, our behaviors represent us, and as such are our beliefs in action. Indeed, our lives are driven by what we believe: we choose mates and friends; raise our kids and choose professions and mates according to our values.

Every day we wake up with the same foundational beliefs. It’s the criteria we make decisions from, how we judge what we read and hear, and what our brain uses to monitor and regulate all incoming content to keep us congruent. Unless there’s specific circuitry to translate incoming content into understanding or action, new information risks offending an unconscious belief and may not be understood or retained.

In fact, unless our brain notices an incongruence it will keep doing whatever it has always done to maintain the status quo. One of the ways it does this is by ‘hearing’ only what we already have circuits to translate, automatically filtering all incoming sound vibrations and deleting/altering them in a way that will sustain or defend our system. So if we hear something we unconsciously find harmful, or have no existing circuitry to translate, our brain will automatically mishear or resist it.

To best understand how our brain translates what’s been said and how this applies to training, I’ll delve into how brains listen. Note: my book WHAT? Did you really say what I think I heard? explains how brains listen and how to mitigate the inherent problems.

LISTENING AND BRAIN CIRCUITRY

Learners and listeners only hear, store, and retain knowledge via their brain’s existing neural circuits.

- Brains may not translate incoming words according to the intent of the speaker making ‘understanding’ uncertain.

- Incoming information doesn’t automatically cause brains to acquire new neural circuitry; it may be rejected if it seems to threaten our beliefs (Note: my book HOW? Generating new neural circuits for behavior change, learning, and decision making explains how brains generate neural circuits.).

The physical act of listening is devoid of meaning:

Listening is an automatic, electrochemical, biological, physiological process during which words, as incoming puffs of air, eventually get translated into meaning via existing neural circuitry. This means we can only understand some fraction of what a Speaker intends – especially when the words or ideas are unfamiliar – and even this is biased by what we already know, what we already have circuits to translate.

With words being meaningless sound vibrations until they’re translated by existing circuits, everything we hear is biased by what we’ve heard or experienced before. This is one of the factors that makes it difficult for Learners to learn.

For those who want the science on this, here’s some general knowledge about how brains listen.

How Brains Determine Action

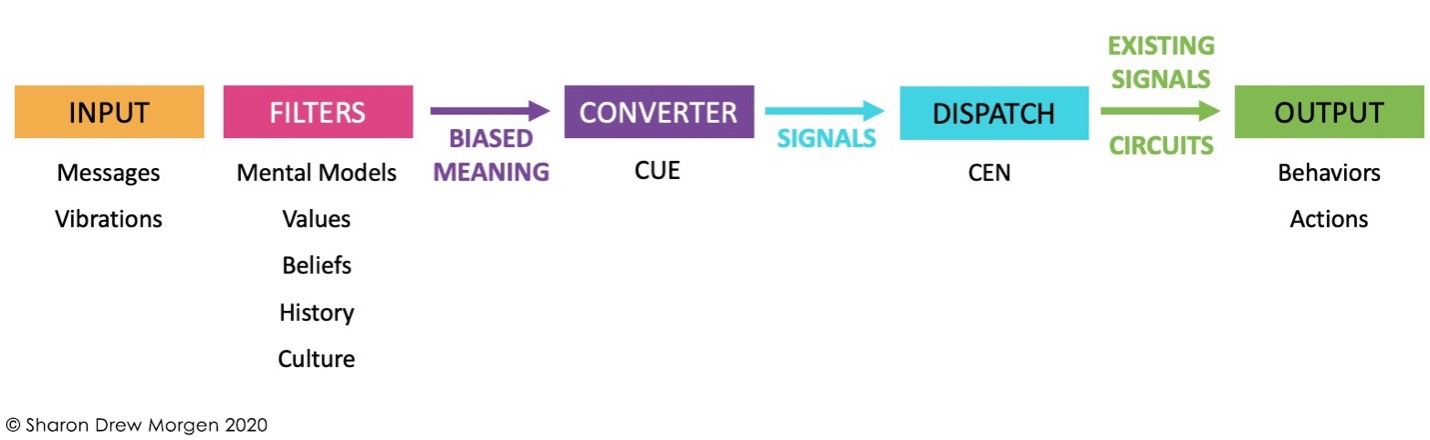

Figure 1: How Brains Listen

Let me explain Figure 1.

INPUT: Sound vibrations enter ears (in this case, through words).

FILTERS: Incoming vibrations get deleted or changed according to our beliefs (Dopamine).

CONVERTER/CUE: Remaining vibrations get transformed into electrochemical signals.

DISPATCH/CEN: To ascribe meaning or action, the Central Executive Network dispatches incoming electrochemical signals to a ‘similar-enough’ set of existing neural circuits among a brain’s 100+ trillion circuits.

OUTPUT/LEARNING: On arrival in these ‘similar-enough’ circuits, the signals go through another deletion and addition process to make sure the incoming signals ‘fit’ that circuit exactly. What’s left is what we think was said.

As you can see, ultimately, Learners have no way of knowing that what they’ve ‘heard’ isn’t accurate.

All of this is going on automatically and unconsciously, in one five-hundredths of a second. A haphazard process at best – one we have no control over as it’s mechanical, automatic, physiological, electrochemical, and idiosyncratic. And without meaning until the very end.

In other words, whatever Learners think they’ve heard, whatever their brain has translated for them, is some translation from where the incoming, compromised, sound vibrations ultimately end up, making it likely that Learners misunderstand, overlook, misappropriate, or mistranslate the incoming content automatically.

In summary, incoming words go through several deletion processes in the brain before they’re translated into meaning according to existing circuits, making it difficult to know what Learners actually hear. When Trainers begin training sharing information or practice instructions, there’s a good chance our important messages have been biased, and potentially misunderstood or unconsciously rejected.

But there’s a way to facilitate learning by enabling Learners to first generate wholly new neural circuits that will hold, accurately translate, and retain new knowledge.

TRAINING AND THE BRAIN

As you can see, learning is more than an information exchange and practice issue but a circuit generation issue. To address this, it’s possible to either

- engage the appropriate parts of the brain before offering data or, if there are no existing similar circuits,

- generate wholly new circuits that will hold and retain it.

By including brain-change in our learning modalities, it’s possible to increase the success of training.

The Learning Loop

To generate new neural circuits, Learning Facilitation begins by 1. following the brain’s steps to install new circuits before offering the new knowledge; 2. isolating the Learner’s brain from their mind. Using the above brain graphic, here are the elements the brain needs to add a new circuit:

How Brains Determine Action

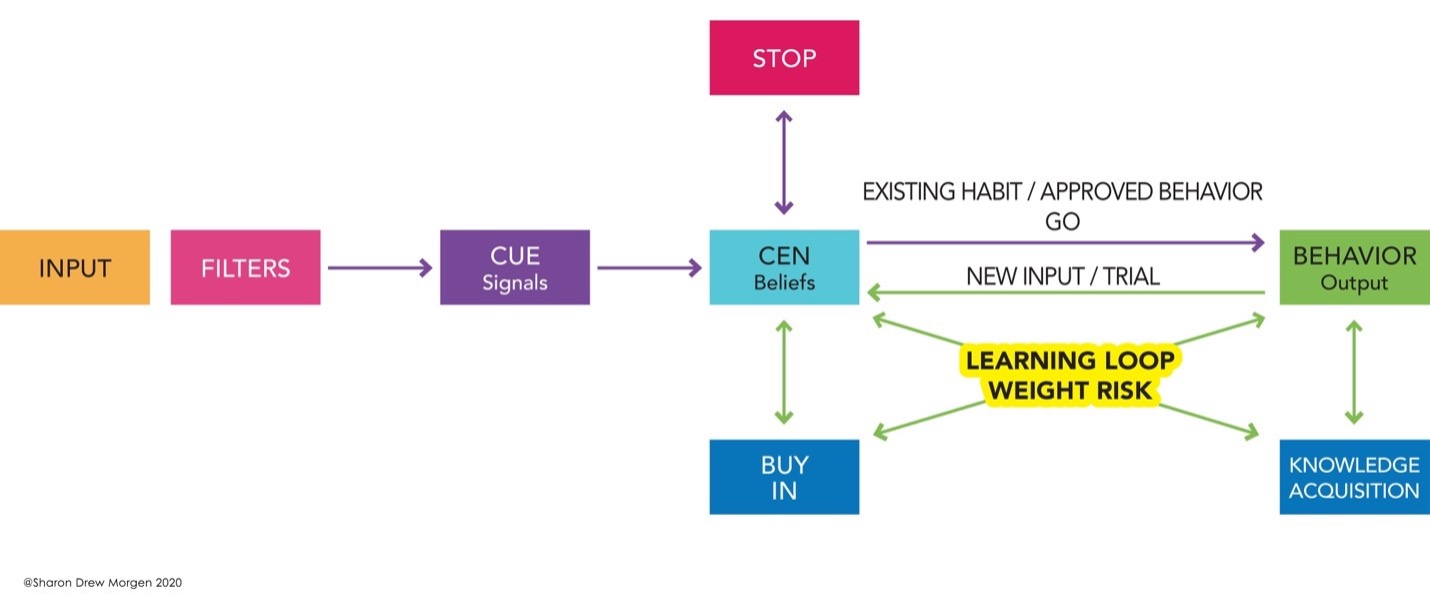

Figure 2: Steps of Learning

The Learning Loop is an iterative process (Figure 2)that progresses between several elements in a way that’s unique for each Learner and include:

- beliefs

- knowledge acquisition (training, coaching, reading, etc.)

- trial/fail/stop

- buy-in

- behavior (the final output/action/understanding)

I’ll explain them individually.

Beliefs: To maintain Systems Congruence, everything we do must be a representation of who we are and what we believe. Therefore, anything we want to do that’s substantially different from our established activity must match our values. So: A vegan will resist learning about cooking a steak, for example.

As most of our beliefs are unconscious and the culprits behind how our brain triggers actions, Learning Facilitation leads Learners to any unconscious beliefs that might jeopardize new learning. This is one of the main factors we must manage in instructional design.

Knowledge acquisition: Learners have different learning styles. Sometimes they require different types of knowledge input to build new circuits, and sometimes they must find existing circuits to match the input. The steps in the Learning Loop are iterative, enabling Learners to determine their own unique choices.

Trial/fail/stop: Learning involves challenges to the status quo. How do Learners accept the new if it differs from their automatic responses? Do they throw away the old or just modify it? Do they need new habits? Since failure is a part of learning, what’s the difference between going through rounds of failing before succeeding vs stopping at the first sign of failure?

Recognizing when, if, and how to continue through the failing/trialing/stopping process is a belief issue. As you’ll see, it’s possible to build this in as part of the learning to ensure the ‘stop’ isn’t permanent.

Buy-in: to retain new knowledge, it must be congruent with our belief system or it will be rejected and resisted. Without congruency, no new circuits will be built, no buy-in will occur. As a training program progresses, there must be ample opportunity for trial and failure for the Learner’s unconscious system to test the new and ultimately buy-in to change.

Behavior: This is the final action – the output, the understanding, the behaviors – instigated by the new circuitry. This must be practiced so the new circuit gets used enough to become a ‘go-to’ place (a superhighway) for the CEN to dispatch the electrochemical signals and prompt the new learning.

This is an iterative process. You’ll notice that the flexibility of the exercises enable Learners to use the sequences that work best for them.

PREPARING LEARNERS FOR A DIFFERENT EXPERIENCE

Different from standard course designs, and because the first task is to generate neural circuits in the Learner’s brain, Learning Facilitation bypasses the mind, avoiding automatic associations, discernment, opinions, and comparisons. With no direct line to ‘thinking’ until new circuits have been installed, the course design provokes confusion and failure as a learning tool, which I get Learners to buy into (see below).

It’s only after new circuits are installed that the new information is presented. As such, the room and requirements are set up in an atypical way: room set up, instructions, and specific types of exercises are designed cause Learners to discover incongruences which then provokes their brains to generate new circuits. I’ll take them one at a time.

Room Setup

NOTES: In a Learning Facilitation setting, we work to initially bypass the mind to minimize internal or external bias. That means no introductions and no notetaking at first.

Notetaking involves Learners matching an incoming idea with existing circuits and familiar ideas. In other words, it involves their mind and a potentially inaccurate translation of what’s been said. Plus, the Learner isn’t hearing the rest of the sentence being spoken as they write. Remember: the first job is to bypass the mind. So: no notes until the Learner has generated new neural circuits.

SEATING: My classrooms use only chairs in a semi-circle with no desks, no computers, no paper/pen in the ‘brain change’ portion of the course. Again, with a focus on brain circuit creation, nothing is needed other than the Learner’s brain.

NAMES: Because Learning Facilitation seeks an environment with minimal bias, Learners only have name tags with their first names. There are no introductions. During the program, everyone becomes familiar with each other as they learn together.

Instructions to Learners

CONFUSION AND FAILURE: When standard training models offer new information first, Learner’s brains may not have the requisite neural setup to translate it accurately and will either misinterpret the new, or experience confusion or failure when they attempt to understand. For me, confusion and failure are positives: they tell the Learner precisely where they’re missing something and points to an incongruence that their brain would like to resolve. And systems don’t like incongruences.

To that end, I tell the class that I’ve built in confusion and failure as features! I promise them that by the time they leave the confusion will be gone and they’ll experience failure as a positive. In fact, I tell them I’ve developed many of the exercises to cause confusion and failure to aid their learning but will discuss their confusion if they’re overwhelmed.

In every program I’ve trained over 40 years, Learners invariably begin laughing at themselves and each other by the afternoon of Day 1. “Sharon-Drew: you’ll be SO proud of me! I’m SO confused!!!” and everyone laughs, together. So trialing, failing, and confusion are built in and Learners are fine with it. It also helps build group dynamics and gives them the freedom to take risks during exercises.

Note: by forcing Learners to fail in front of their peers – who are also failing – during exercises, with the stigma of failure removed Learners use ‘failure’ as one of the stepping stones to their learning.

QUESTIONS: At the beginning I avoid offering information as my answers won’t be heard accurately and merely causes resistance, albeit unconsciously, when it is different from what the Learner has been doing habitually. And since questions are triggered by the mind when it compares what’s already there against the new, I tell Learners that I may not directly answer a question at the beginning but point them to where their question arises from. So:

Question: “I’ve always done X. Will I have to alter that?”

Response: “What I hear you saying is that X has been your go-to response. What would you need to believe differently to be willing to do something else?” or “Has that worked well-enough for you to not consider adding anything different?”

Remember: I’m working first with the brain; as mechanical and electrochemical organs without meaning, brains have no questions! Once we’ve gotten to the halfway point in the program, I do answer questions with information.

Instructional Design

Learning Facilitation uses exercises and questionnaires to separate the Learner’s brain from their mind, discover incongruences, and enable them to make conscious choices instead of acting unconsciously:

- exercises that highlight the brain’s automatic responses so they can notice what’s not working and the precise incongruence they need to change. During the exercises, I go around the room touching Learner’s shoulder and making corrections without comment, providing an example of a successful response they hadn’t considered, and then walking away. While this doesn’t teach them what to do, it provides an example of the new idea at the moment the brain is experiencing confusion.

- post-exercise questionnaires to put the Learner into Meta/Observer/Witness. This helps them circumvent their brain’s automatic, habituated response; creates a distance from any feelings of failure; and broadens the range of choice. And Learners get to keep these to peruse after class.

These questionnaires enable Learners to capture their unconscious choices and highlight what they think happened during the exercise.

I use two types of questionnaires: a general one that elicits reflection for both sides of the interaction (i.e. from their partner’s side as well) to begin noticing what, specifically, they did that worked vs what didn’t work; and one that puts them into an objective, or Meta/Observer/Witness standpoint, so they experience an unbiased, dispassionate viewpoint to notice the broader implications.

Examples of the general questionnaire following an exercise in which the Learner takes both the Seller and the Buyer roles:

You as the Seller:

-

-

-

- Did you achieve what you sought out to achieve? Why? Why not?

- On reflection, what would you have liked to have done differently?

-

-

You as the Buyer:

-

-

-

- How did the interaction feel to you? Were you respected? Did you feel heard?

- What stopped you from buying what the Seller was selling? What would they have had to do differently to get a different response from you?

-

-

Examples of the objective questionnaire that gives them distance and the ability to notice incongruencies:

On reflection

- when taking the Seller’s role, what specifically did you do or say that caused success? Failure?

- looking back at the entire exercise, what might you have done differently to generate a more successful interaction? What stopped you from doing it? What would you have needed to know or do differently from having a different outcome?

- how did you choose to listen for what you listened for? What did you miss at the time? What might you have listened for to obtain the full fact pattern?

- when responding to your partner, what components of their communication did you attend to? Did you disregard? What would they have needed to do differently to prompt a different response from you? What would you have needed to say differently to prompt a different response from them?

These questionnaires go a long way to providing the Learner an awareness of their unconscious choices. Without this awareness, they might rationalize the outcomes of the exercise or make flawed assumptions. These questionnaires start the process of generating new neural circuits as the Learner begins to notice incongruences and how their choices specifically lead to their outcomes.

- build in failure so Learners become aware of any incongruences that the new learning would improve. For this I put them into small (4 people max) groups and have them do something that the new material teaches, but they don’t know how to do yet. In other words, they’re set up for confusion and failure – a route to discover incongruences and generate conscious awareness.

I have the group members track each other and raise a hand to tell the speaker if they’re getting the instructions wrong and then offer another approach, to which the other group members also notice if something could be better with the response. In this way, all group members attend each other’s responses very carefully, are all willing to get it wrong, begin to recognize better choices, and begin noticing that their natural inclinations are problematic… unconscious incongruences that have become automatic and need to change.

- open frame for integration after each long break: at the start of each day and after lunch I build in a 90-minute open frame except for Day 1 when I allow 45 minutes to check in with their level of confusion and well-being after lunch.

- I offer short procedural lectures during the brain segments (in my programs that’s until mid-day Day 2 when they have neural circuits in place and I begin lecturing on the new material).

To lessen confusion at the beginning, these brief lectures offer standard ideas not being taught per se but make the following confusion manageable. I might give a procedural lecture on how brains listen or store information; or what bias is and where it comes from. But I wait until at least midway through the program to offer information-rich lectures, during which time the Learners can take notes.

CONCLUSION

Learning Facilitation is an addition to current information-based training models, to produce a home in the brain to retain the new learning. It uses different goals and room set up, and utilizes exercises, questionnaires and confusion/failure to separate the brain from the mind to generate new neural circuits.

Learning Facilitation is a systems-change and risk management model. It prompts Learners to recognize their incongruences and build neural circuits before offering information per se. Once this is accomplished standard instructional design takes over.

ACKNOWLEDGEMENTS. As an original thinker, I think in systems and read broadly to stimulate ideas regarding how brains accept, transmit, and transfer signals for action. I’ve read over 1000 books and articles, research papers and abstracts, on how brains work, and written 10 books on the facilitation models I’ve invented to make conscious brain change in change, sales, leadership, and communication. The field of Neuro Linguistic Programming (NLP) has helped me understand the full extent of how systems operate. I owe the field a huge debt of gratitude for helping me organize and compare content.