When groups seek change – when considering purchasing a new solution, shifting strategies, reorganizing, for example – they need consensus. When families discuss putting a family member in a home, or start-ups decide to seek funding, they need consensus. How do groups achieve an outcome acceptable to all when their beliefs, goals, or convictions may be disparate?

When groups seek change – when considering purchasing a new solution, shifting strategies, reorganizing, for example – they need consensus. When families discuss putting a family member in a home, or start-ups decide to seek funding, they need consensus. How do groups achieve an outcome acceptable to all when their beliefs, goals, or convictions may be disparate?

While every group is different and each goal unique, the consensus meta-process is the same: the right people must

- be convened,

- approve the elements of the issue to be decided upon,

- find their way to agreement.

There are problems lurking at each stage:

- Gather the right people. Not as easy as it sounds. If there is no existing group, say a Board or a City Council, what mix of people would successfully represent the community? How can the right team be chosen to carry the voice of a new decision? In my experience, sometimes choosing the ‘right’ people is a political decision and too often excludes folks with an important voice.

- Include the appropriate elements to be decided upon. This is the biggest area of struggle: the correct criteria for agreement ends up being defined by folks with potentially divergent outlooks. Who gets to designate the acceptable criteria – and what is the cost of overlooking those unheard? Again, too often this decision is front-loaded, with the loudest voices carrying the most votes, and some important elements are ignored.

- Reach agreement. Members of the decision team may have unique – and potentially opposing – criteria. How will the group ensure the final outcome is an accurate indicator of the population and good-enough to be acceptable, while addressing each member’s values during the process? Until the outcomes and representative values of the group members – often hidden – are addressed, the search for agreement is a struggle.

BIASES ALTER REALITY

Unless it’s a small, homogeneous group, an outcome fully agreeable to all is pretty rare. Each member perceives problems and solutions according to their unique biases – individual beliefs and maps of the world – driving them to compete to be the arbiters of the group’s reality. And once members begin arguing about who’s ‘right’, some with softer voices may get overlooked.

From the studies I’ve read, group members are more willing to buy-in to an idea they are not fond of if they have had a chance to express their beliefs, ideas, and disagreements, and feel heard. How do we hear the full range of possibilities if we are each listening through our own biases? We don’t. So we need to listen differently.

In my new book What? Did you really say what I think I heard? I illustrate at length (from several expert sources) how close to impossible it is for anyone to accurately hear what another person means to convey. Sure we ‘hear’ the words. But we regularly misconstrue the intended meaning because our biases, assumptions, triggers, memory patterns, and habits, automatically filter out words or ideas that offend our status quo, leaving us with the residue that we mistakenly believe is what was said – some percentage of what the speaker meant to convey. Makes it hard to find a path acceptable to all.

One way to help achieve that is to listen differently: it’s more likely to hear accurately by listening for more generic, acceptable themes, ridding the conversation of the bulk of the biases. So if an HOA seeks consensus on mandating guards at the resident’s doors during parties, for example, a general theme might be Building Safety. Once Building Safety is agreed on as necessary, then ways of being safe and responsibility for safety, might be discussion topics. Similarly if a group of hospital administrators seek upgrades to their technology amidst great contention, the ‘chunk up’ might be the need to capture patient data accurately and work backwards from there.

To accurately hear what our colleagues mean, we might shift our focus from

- promoting an idea, to encouraging win-win,

- getting agreement through compromise, to discovering how all voices can be heard,

- seeking a specific change, to collaborating around a more generic concept.

Then we have a better shot at achieving solutions that include creative ideas and acceptance from everyone. And everyone gets heard.

____________

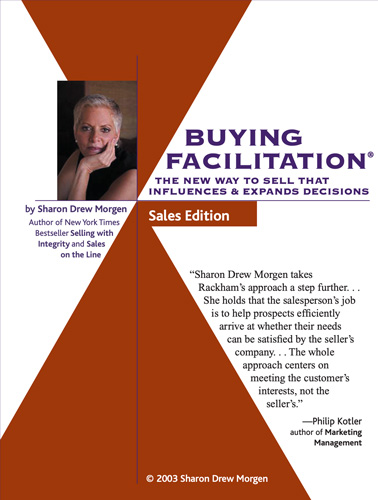

Sharon-Drew Morgen is the NYTimes Business Bestselling author of Selling with Integrity and 7 books how buyers buy. She is the developer of Buying Facilitation® a decision facilitation model used with sales to help buyers facilitate pre-sales buying decision issues. She is a sales visionary who coined the terms Helping Buyers Buy, Buy Cycle, Buying Decision Patterns, Buy Path in 1985, and has been working with sales/marketing for 30 years to influence buying decisions.

More recently, Morgen is the author of What? Did You Really Say What I Think I Heard? in which she has coded how we can hear others without bias or misunderstanding, and why there is a gap between what’s said and what’s heard. She is a trainer, consultant, speaker, and inventor, interested in integrity in all business communication. Her learning tools can be purchased: www.didihearyou.

She can be reached at sharondrew@sharondrewmorgen.

1 thought on “Consensus: From Biases to Buy-in”

Send Valentine’s Day Flowers to Germany with

the assistance of online shopping store and add extra charms and beauty to the

celebration. Valentine’s Day is the day where people express their love in very

exclusive way.