Change involves very specific stages, all necessary to achieve congruency and acceptance by the underlying system.

During the course of my life study of brains and change, I’ve unpacked the elements necessary before we take on new behaviors, or make decisions that will cause us to change in any way. Indeed, there are 13 stages of change, and they’re systemic. I’ll begin with my definition of a system and then explain the stages I’ve unpacked.

WHAT IS A SYSTEM AND WHY DOES IT MATTER?

A system is a group of interrelated elements that all buy-in to the same rules – endemic rules that are often unspoken yet are the foundation of the culture and expected behaviors. Obviously working at Google will have a different system than working at IBM. A family in rural USA will have different rules than folks living in Paris.

We are all systems, both personally and in our work and family lives. A system is comprised of rules, beliefs/values, norms, history, culture, mental models that create and maintain the status quo, the identity. They dictate our choices of fashion, mates, professions, politics – even where we live and how we listen.

One of the features of systems is their need for consistency to maintain itself over time. This is called Systems Congruence. And this is the underlying factor in change. Everything we do must meet the unconscious rules of our system.

CHANGE IS SYSTEMIC

Recognizing the system as the foundation of who we are and our behaviors, I realized early on that making a change, doing anything different – even adopting new ideas – risks causing imbalance, incongruence, to a system which will fight to maintain its status quo (Homeostasis). How, then, do we do anything different and still maintain congruence?

After thinking about this for some time, I unpacked what goes on during a change process, a process where we end up with new choices, new behaviors, new outcomes. Where to move and which house to choose? Take a new job? End a fight with an old friend? So much of what we do involves us choosing one thing over another. I’ve broken down the steps so we can do this consciously and congruently. I’ll start with my foundational thinking:

- Since systems must remain congruent (or we live with resistance, incongruence, confusion), we can’t maintain anything ‘new’ if it’s being rejected or denied. That means the new elements must match the ‘givens’ that the ‘new’ will replace. Obviously, it’s important to know the full fact patterns of the status quo to know what the new must match. I call this understanding the Present State:

- What are the current ‘givens’ of the status quo in relation to the proposed change? What is in that same ‘space’ where the new would fit? What are the components that maintain it within the system?

- All components of the Present State must be understood so the ‘givens’ are maintained and their underlying norms not compromised.

- Shorthand: Where are we (i.e. What is the Present State?)

- For a system to be willing to add/subtract an element in an area that’s already a normalized part of its functionality, there must be a recognized incongruence. If all is believed to be OK, and the system recognizes no incongruence, it will not seek change. Whether or not the system is functioning optimally is not in question: it’s dependent upon whether or not the system is congruent according to its own norms. (I.e. a man who has been 400 pounds for years is congruent since the system has already normalized the ‘givens’ that maintain the status quo.)

- Does the system recognize a missing component?

- Once something missing is acknowledged, the system MUST fix the problem or admit incongruence.

- Once all ‘givens’ are involved and known, anything missing will be obvious.

- Shorthand: What’s missing?

- Since the rules of each system are idiosyncratic, each system will first try to fix its incongruences itself or with familiar resources that have already been agreeable to the system. Anything from outside risks disrupting Systems Congruence.

- It’s only when a system cannot fix its incongruence that it will consider change. The first step is to try to fix the incongruence.

- Shorthand: How can I fix the problem myself (or with known/already accepted resources)?

- Once a system has recognized an incongruence and tried to fix it itself or with known resources, AND it has not been able to fix it, then it MUST seek an external solution. Systems don’t like incongruences as they seek Congruence.

- Since external solutions rarely carry the same rules, norms, or beliefs as the underlying system, adding something new will cause some level of disruption. Unless the system understands the extent of the disruption, the ‘cost’, that the new will cause, it will resist and make no change.

- The ‘cost’ of the new must be equal to or less than the ‘cost’ of the problem or it will be deemed too ‘expensive’ (i.e. disruptive) and not be adopted and be rejected.

- Shorthand: What is the ‘cost’ of the change? What considerations must be managed so the system will adopt it? How can everything and everyone that will touch the bit that needs changing buy-in to accepting the new?

- It’s only when a system cannot fix its incongruence that it will consider change. The first step is to try to fix the incongruence.

- Does the system recognize a missing component?

- What are the current ‘givens’ of the status quo in relation to the proposed change? What is in that same ‘space’ where the new would fit? What are the components that maintain it within the system?

The baseline idea here is that no change – no buying, no new habits or behaviors – will be accepted, regardless of the problem, the need, or the efficacy of the solution, unless the system ends up congruent.

It doesn’t need to end up the same, but it must employ the same rules, values, and norms of the system.

THE STEPS OF SYSTEMIC CHANGE

Obviously, when we consider a new decision and need to weight options, we may not come to a conclusion until all, or most, of our unconscious criteria are met. This usually takes some time. Using my Decision Facilitation model – the steps of change plus Facilitative Questions – it’s possible to traverse the path to a new choice very quickly as all of the underlying and usually unconscious givens will be known.

I’ve unpacked 13 steps that all change, choice, and decisions take, occurring in a very specific order, in order to remain congruent:

1. Assemble full representation to agree on purpose and goal

- Ask: what would you have now if all you need would be in place?

- Iterate until across-the-board agreement. Chunk-up where necessary.

2. Discuss possible implications – risks, readiness, disruption – for change.

- Ask: what would cause you to not attain this now?

- Iterate until all voices express their doubts, fears, problems

3. Consider risks of change to attain new goal. What’s needed for buy-in?

- Brainstorm: what would change? cultural norms? Individual jobs? Timing? Finance?

4. Identify the risks of each proposed change: What is the fallout? How can we achieve buy-in without resistance?

A. If risk worthwhile, reach consensus re beliefs, values, norms, that must be upheld in a solution.

- Ask: who are we as a group/company that must be maintained?

- Iterate until a set of beliefs, values, norms etc. are agreed

B. If too risky, is there a way to make less risky changes that match beliefs and meet goals?

- Ask: who are we as a group/company that must be maintained?

- Ask: what goals can we meet with manageable risks?

- Get agreement from stakeholders involved with proposed changes.

5. Get stakeholder agreement on goal. Brainstorm outputs/behaviors to meet.

- Check they match the group’s values. Get agreement to proceed.

6. Brainstorm possible new outputs/behaviors to match beliefs/meet new goals.

- Ask: what new behaviors/actions would match our beliefs and resolve the problem? Do they match our values? What would we do/have differently? How will we manage the risks of each?

7. Confirm buy-in by all who will touch the new solution before implementing.

- Is risk managed? Are stakeholders on board for each change? are values incorporated?

8. Form implementation groups.

9. Brainstorm/research what stakeholders in each department/ group must add/shift to achieve goal.

10. Full representation of voices to choose the best resources to achieve goal.

11. Brainstorm what’s necessary to learn/implement/maintain resources.

12. Choose leaders to manage implementation/maintenance of new resources.

13. Decide on how follow-up will be managed.

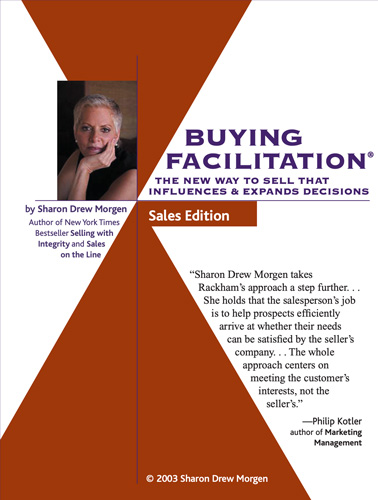

These are written with ‘team’ or ‘group’ steps but obviously the same for individual use as well. The point is: change and decision making uses each of these steps are handled (and sometimes they’re iterative) or the system will believe it’s at risk and any change will be resisted or will fail. I’ve applied this model to sales (Buying Facilitation®) and behavior change [link to How of Change topic section] and use it in coaching, leadership, and any sort of personal habit change.

When I’m coaching, or leading a group through change, or facilitating people through their change management issues before they become buyers, I use Facilitative Questions to lead folks through to decision making and change. I actually have a set of audio tapes where you can listen to me formulating the questions and using the 13 steps.

Unfortunately, coaches, leaders, and sellers have been trained to use their own knowledge and curiosity to pose questions and inspire change. As I’ve said, that’s not only biased, but doesn’t comply with the format, the trajectory, of how brains change. It’s far more targeted to use the steps of change I developed as people can match their behaviors with their brain set up and the process will be smooth.

To learn the Steps, go to Applications.

Or contact me with questions: sharondrew@sharondrewmorgen.com